I've always loved Georgette Heyer, but I never used to talk about it much.

However, as time passes, I'm becoming more open about my socially unacceptable side. I am now happy to admit:

1) I hate cats (and although I'll probably pretend to believe your cat is cuter, fluffier, more super-smart than any other cat, I will still hate it).

2) Sorry, but I have absolutely no idea when anyone else's children's birthdays are - I have enough trouble remembering all their names.

3) I spend a lot of time, while talking to other people, thinking about how to escape.

4) I love regency romances, particularly Georgette Heyer's.

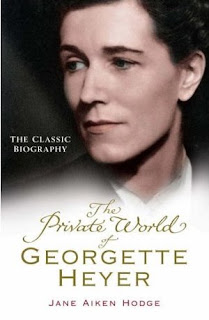

So, it was without shame that I took a Heyer biography out of the library last week. And, it is equally without shame that I note down a few facts that I found interesting:

- Born 16 August 1902, she published her first book (The Black Moth) when she was only 19 - it was a story she had made up to amuse her brother, Boris, who was a haemophiliac and spent a lot of time convalescing.

- She suppressed her 4 early 'straight' novels (all focused on the class structure of English Society): Instead of the Thorn (1923), Helen (1928), Pastel (1929) and Barren Corn (1930).

- She found men more interesting than women who either talked of nothing but 'servants and the weather' or worked and suffered from 'a magnified sense of their own importance.'

- She was also a devoted spectator sportswoman and loved golf and the Test Match.

- In 1925 her father died of a heart attack, leaving the family with no finances, so Georgette Heyer became the family's main bread winner (putting her brother Frank through school and Cambridge Uni). Her brother, Boris, and her mother, would always need her financial support.

- She married Ronald Rougier (a lawyer who became a QC in 1959) just two months after her father's death and the marriage lasted nearly fifty uneventful years .... 'happy the marriage that has no history'

- The success of her early books without any publicity demonstrated the public exposure she shrank from was unnecessary (although, had she met the critics, her immense personal style might have suggested her books were more than mere romantic cliche). She said later: 'As for being photographed At Work or In My Old World Garden, that is the type of publicity which I find nauseating and quite unnecessary. My private life concerns no one but myself and my family; and if, on the page, I am Miss Heyer, everywhere else I am Mrs Rougier, who makes no public appearances and dislikes few things so much as being confronted by Fans. There seems to be a pathetic belief today in the power of personal publicity over sales. I don't share it... Console yourself with the thought that my answers to the sort of questions Fans ask seem to daunt them a bit! Not unnaturally, they expect me to be a Romantic, and I'm nothing of the sort.'

- Books like The Conqueror (1931) show her as a master of military strategy.

- 1932 she gave birth to Richard George Rougier ('my most notable (indeed peerless) work').

- She aimed to produce one historical and one detective novel a year.

- Her husband collaborated in the detective novels and would provide the plots, while GH developed the characters and relationships... She later declared, ''Why Shoot a Butler?' is so complicated it baffles me.'

- She kept reams of notes and background detail and slang in Regency life. She dates her books effortlessly with a casual reference to contemporary event, e.g. The Foundling's reference to the Prince Regent sets the book after 1811 and one to Princess Charlotte's death in childbirth places it after 1817. However, her files do not mention sources - she was a collector rather than a scholar.

- Many, including her family, think An Infamous Army GH's best book - she uses Wellington's own letters and reported speech to portray him.

- She mocked her own heroes: Mark II - 'suave, well-dressed, rich and a famous whip'; Mark I - 'the brusque, savage sort with a foul temper.'

- Equally true of her heroines: Mark I - a tall young woman with a great deal of character and somewhat mannish habits; Mark II - a quiet girl, bullied by her family, partly because she can't bear scenes.

- Faro's Daughter (1941) has one of her most elegantly worked out plots (and a Beatrice v. Benedick central relationship).

- Penhallow (1942)began, 'Jimmy the Bastard was polishing the shoes'. It was intended as a contract breaking book and was duly turned down by Hodder. It was also the last detective story she wrote for 5 years.

- GH has described Friday's Child (1944) as 'my own favourite', and says that The Unknown Ajax and Venetia are 'the best of my later works'.

- She had a letter from a Romanian political prisoner who kept herself and her fellow prisoners sane by telling the story of Friday's Child over and over ('as I have a very retentive memory I was able to tell it ... practically verbatim').

- GH often accused of repeating herself, and Spring Muslin is at once a classic case and a demonstration of how little it matters. Amanda and her Brigade-Major owe a great deal to Juana and hers in The Spanish Bride, & Amanda's relationship with the poet Hildebrand harks back to Pen Creed's with her childhood sweetheart in The Corinthian and Cecilia's with Augustus Fawnhope in The Grand Sophy. These are themes, used just as Mozart used themes from Figaro to make a point in Don Giovanni.

- Many battles with the Inspector of Taxes.

- Like many remarkable people she needed comparatively little sleep - her son remembers her writing into the night and still leading normal life of wife and mother in daytime.

- Men as well as women read Heyer, and not just the detective stories. Lord Justice Somervell bequeathed his Heyer collection to the library of the Inner Temple Bench, an unusual accolade for a romantic novelist.

- GH had a wonderful way with irony, ref. Frederica:

Lady Buxted's disposition was not a loving one. She was quite as selfish as her brother, and far less honest, for neither acknowledged, nor, indeed, recognized her shortcomings. She had long since convinced herself that her life was one long sacrifice to her fatherless children; and, by the simple expedients of prefixing the names of her two sons and three daughters by doting epithets, speaking of them (though not invariably to them) in caressing accents, and informing the world at large that she had no thought or ambition that was not centred on her offspring, she contrived to figure, in the eyes of the uncritical majority, as a devoted parent.

- She also made numerous attempts at literary criticism, but few got published (the suggestion is that her fame as a romantic novelist militated against her). One impressive piece is about Mr Rochester:

Charlotte [Bronte] knew, perhaps instinctively, how to create a hero who would appeal to women throughout the ages, and to her must all succeeding romantic novelists acknowledge their indebtedness ... He is the rugged and dominant male, who yet can be handled by quite an ordinary female: as it

might be, oneself! He is rude, overbearing, and often a bounder; but these blemishes, however repulsive they may be in real life, can be made in the hands of a skilled novelist extremely attractive to many women ... She doesn't allow Mr

R's rudeness to take the form of unendearing vulgarity, any

more than she permits his libertine propensities to show themselves, except in retrospect... She had the genius to state that he was not a handsome man, thus lifting him out of the ordinary run of heroes. What, in fact, did this ugly hero look like? Had he a squint or a harelip? CB knew her job better than that! 'He had a dark face, with stern features and a heavy brow.' Promising we think, already a little thrilled. But what were his defects? We learn that he had a chest too broad for his height, and find nothing to disgust us in this. Nor is it long before we read of his 'colourless, olive face, square, massive brow, broad and jetty eyebrows, deep eyes, strong features, firm, grim mouth - all energy, decision, will,' and, like Jane, we succumb to this splendid creature.'